Every watch brand these days dreams of future-proofing its product lineup, but achieving that is often discussed as if it were the Holy Grail of design. And, truthfully, it may well be. It certainly seems as if finding a watch style and a brand image that will forever remain on-trend is impossible, but there are certain established truths brands can be relied upon and of which consumers should be aware before investing their hard-earned cash into any brand. If you want to know if your investment will stand the test of time, it is perhaps more important to look backward rather than forward.

Although fashion tends to be somewhat cyclical in its nature, we cannot predict when something we’ve seen before will return to prominence, or for how long it will remain en vogue. Despite these shifts in taste and stylistic focus, there have been some watch styles that seem able to resist the influences of the world around them, and continue to shine whatever the time.

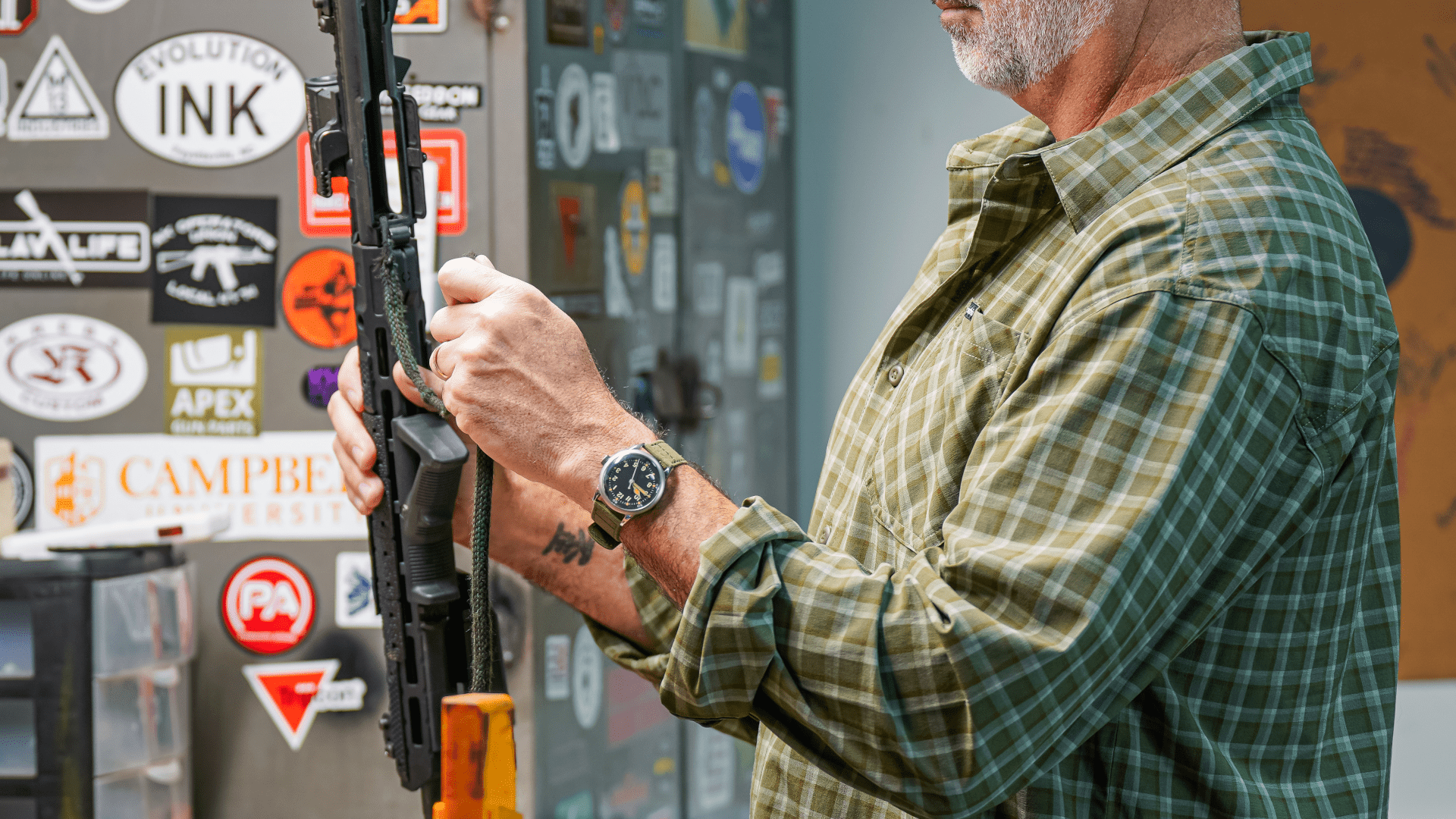

There are some pretty famous examples from major luxury brands (watches like the Rolex Datejust, Omega Speedmaster, or Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, for example), but another style of watch that seems eternally cool is the military-inspired field watch.

There is undoubtedly a lot of emotion wrapped up in the seemingly eternal adoration of the humble field watch, given how it is so often associated with the closing stages of WWII. The famous “Dirty Dozen” watches created by Omega, Cyma, Longines, Grana, Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC, Record, Timor, Buren, Vertex, Eterna, and Lemania, have become legends in their own right, but the fact the small number that made it to the wrists of active servicemen for whom they were intended as the conflict drew towards a victorious close for the Allies, makes them even more special. Many enthusiasts groups have sprung up in the intervening decades, celebrating these icons of design and the part they played in finally winning the biggest and bloodiest war this world has ever seen.

The fact that the legacy of these beautifully designed and exceptionally executed has been so widely covered in the watch world helped establish the specifications laid out for their construction as the starting point for any classic field watch design.

At the same time, on the other side of the Atlantic, the A-11 was in development. Produced originally by Elgin, Waltham, and Bulova for the American Army, the A-11 had its own take on the classic style, choosing to adopt some traits of the even earlier Trench Watches used by military personnel during the First World War. Larger, “cathedral” style hands, and a narrower bezel, allowing for a wider and more legible dial, aids this watch's intended purpose as a navigational tool.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the modern iteration of Praesidus, so dedicated as the brand is to maintaining the spirit and aesthetic cues of the original pieces, should look to reproduce as faithfully as possible the watch that helped the troops involved in the Second World War

Perhaps the extent of the field watch’s current popularity can be put down to the watch industry’s seemingly tireless obsession with neo-vintage pieces. In the 1990s, when luxury watchmaking really started to find its feet and mechanical timepieces once again became the first thing collectors thought of when they thought of good quality timekeepers, styles were bigger, bolder, and brasher than they had ever been before. This era of bombastic communication and eye-popping watch case diameters persisted well into the first and even second decade of the new century before a quiet call for a return to classicism started to emanate from the fringes of the industry.

As the 2010s progressed, we saw more and more brands mine their own back-catalogs in search of the “next” “big” thing, which, ironically enough, tended to be a reimagined, retooled version of an old and much smaller watch.

As diameters returned to less wrist-straining sizes, so too did the appetite grow for more traditional styles. The humble field watch was, thanks to the dial/bezel relationship making the most of the available space resulting in a highly readable dial even at more demure diameters, suddenly back at the forefront of every watch critic’s mind. Over the past ten years, we have seen an immense amount of heritage-inspired field watches making their way to market. The reception? Ravenous. The likelihood of this trend ending any time soon? Low.

It would be fair to ask, however, whether having such robust faith in a style of watch that spent many decades in the doldrums is wise, given how vastly different the tastes of twenty years ago are in comparison to today. Is it possible that mechanical watchmaking will return to the lamentable (and, frankly, quite embarrassing) brazenness of the 1990s? While possible, it seems extremely unlikely given the evolving market conditions, which need to be understood all the way from the field watch’s emergence to the current day if confidence in the field watch’s ability to endure is to be bolstered.

In the 1940s, the Dirty Dozen watches were not collectibles. As handsome as they were, it would be fair enough to say they weren’t even broadly desirable. They were necessary. They were tools refined to perform a specific function. There was no pomp or ceremony about their “release”, and, in fact, they were never actually released to the public for purchase (hence their rarity and enduring mystique. They were there to do a job as well as it could be done and, once that job had been performed, no one expected them to hang around for very long, much less enter the public consciousness as objects that might be viewed as aesthetically peerless design icons.

Even through the ‘50s and ‘60s watches of the Dirty Dozen’s nature were not recognized as the collectible and historically significant timepieces that they would come to be. Watchmaking was yet to experience the notion of luxury. Yes, there were good watches. Everyone in those days regarded a Rolex as a sign of success, and it was customary to buy oneself or be gifted a gold Rolex upon certain milestones in life. The reason why it was so customary, however, was that Rolex watches, while expensive, were not priced out of the realistic reaches of a common man that worked hard and achieved good things. They were significant timepieces but not in the same way they are today. The 1970s would be the decade that started the transformation of the watchmaking industry into the luxury behemoth it is today.

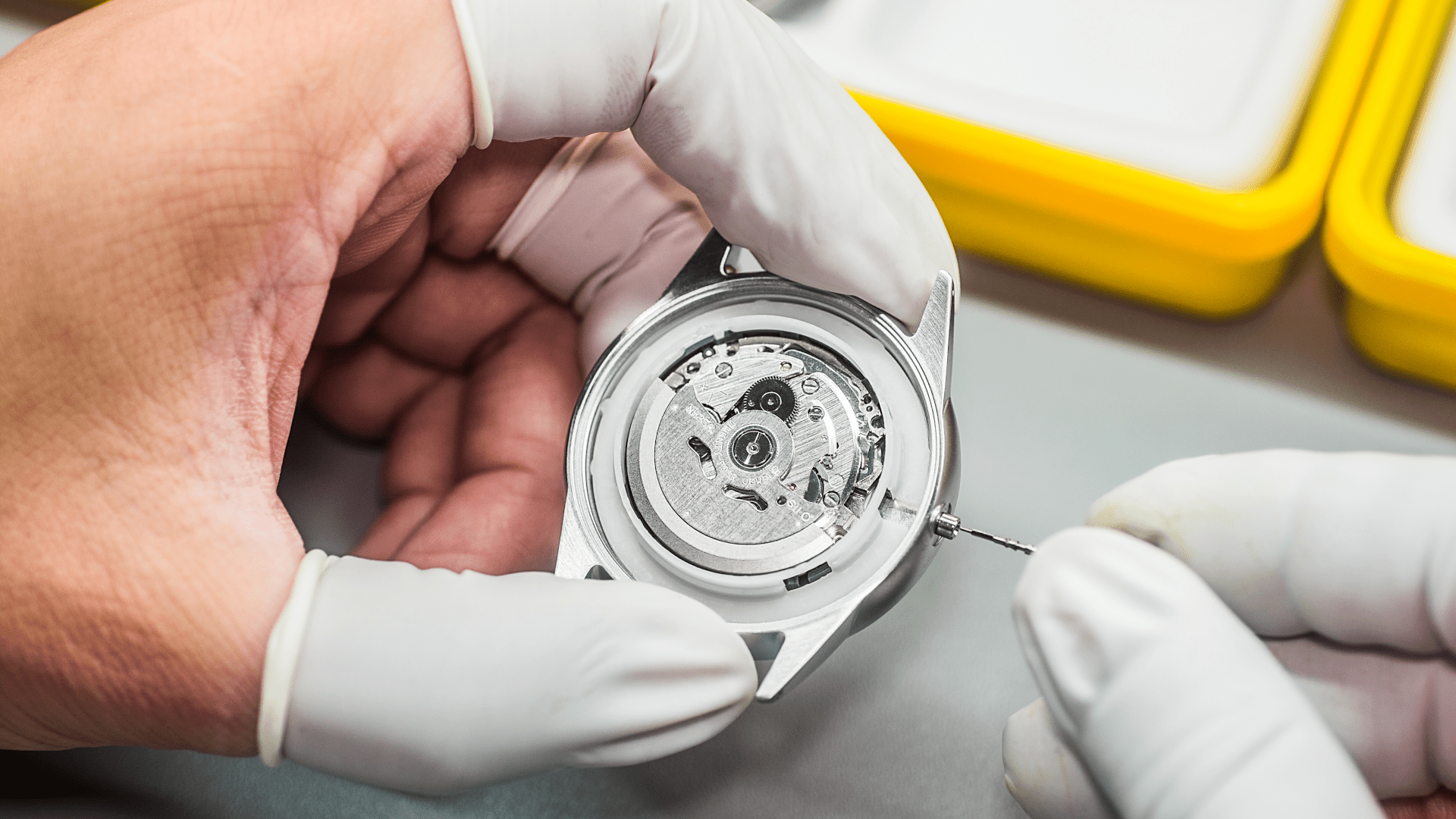

In the 1970s, quartz technology started to emerge. The Japanese had figured out how to create battery-powered watches with a regulating organ far more accurate than the traditional mechanical watch escapement. A small slither of quartz crystal, encased within a slim metal tube would vibrate at an extremely regular rate, almost entirely impervious to shock or temperature fluctuations, and do so without the intervention of a highly skilled watchmaker.

In the early days of quartz technology, quartz-regulated watches were expensive and viewed, perhaps fairly, as the world’s first “luxury” wristwatches (if one accepts that Rolex had not already earned that title after a barnstorming performance throughout the 1950s, releasing a spate of future classics, making peer-pummeling watch design look easy).

Very quickly, however, quartz technology became eminently affordable. So affordable and easy to mass-produce, in fact brutally decimated the mechanical watch industry in a matter of years. It seemed for all the world like nothing but progress. Quartz-regulated watches are cheaper, easier to produce, more accurate, and, in those days, at least, very cool. What wasn’t to like? It seemed clear at the time that the beating hearts of mechanical watches would be forever arrested. But then, in the early 1980s, something very strange happened.

In 1983, the world-famous Swiss brand Swatch was founded. While Swatch watches were (and mostly still are) quartz-regulated themselves, they did two things that no Japanese company had ever thought to do. Swatch made watches cool (or, should that be, Swatch made cool watches). They made watches into affordable, almost throw-away collectibles. The name Swatch, which many people take to be a contraction of “Swiss Watch” is actually a portmanteau of “Second Watch”, as the original pieces were intended as something the gentleman traveler might buy at an airport as he departed on a business trip, preferring to leave his Sunday dress watch at home, safe in his sock drawer.

Swatch collaborated with artists, designers, and celebrities in a move that completely altered the face of the industry. For the first time, people had a reason to buy more than one watch (and were able and encouraged to do so).

The second effect of the Swatch phenomenon was that it retrained the industry’s eyes on Switzerland. Nicholas G. Hayek, the man behind the foundation of Swatch, had been systematically buying up all of the defunct names of flagging survivors of the “Quartz Crisis” that had ripped through the Swiss manufacturing industry in the previous years. He would go on to unite these companies (which included famous brands such as Omega, Longines, Hamilton, Tissot, Certina, Blancpain, and Breguet) under the banner of “the Swatch Group”, which still exists to this day.

Under Hayek’s watchful eye and thanks to his astute mind, Swatch laid the foundations for the return of mechanical watches, now pitched at a higher level of importance. Watches were, for the first time habitually, sold as luxury items (because despite the love and affection that had endured for the hand-crafted aspects of watchmaking, mechanical watches still weren’t as “good” as their quartz counterparts).

This bizarre about turn meant that, in its early days at least, the luxury watch industry had to be very different from what had gone before. Watch cases got bigger. Bright colors entered the fray. Things like eye-watering patterns failed material experiments, and overtly sexualized marketing became the norm. Portraying the idea of luxury was everything. In those days, the way marketing executives and designers decided to do this was to shout at the world from the wrist. Getting noticed was key. Reservedness or humility was not on the menu. The idea back then was that why would anyone buy an expensive watch that nobody knew was expensive? The notion of pure class and stealth luxury were many years of maturing in the minds of those responsible for the output of that decade and the early days of the aughts.

Say what you want about that period of watchmaking’s history, but it worked. It firmly established the separation between the luxury watch market and the quartz market (even though some luxury quartz watches still existed such as the Breitling Aerospace, which has always succeeded in straddling the divide between the two sides of the industry on account of its souped-up quartz module that is thermo-compensated to make it even more accurate than a regular quartz piece, however unnecessary that may be in 99.99% of situations).

Quartz watches were just that — watches. Luxury watches, however, were symbols of status, expressions of personality, and, even, works of art. They were distinct. They were eye-catching. They were worth it. And, as truly awful as many of those more “out there” designs might look to a modern eye, they had a part to play in the golden era of watch design through which are now living.

The designs of the past, such as the Dirty Dozen and the Praesidus A-11, are suddenly able to be realized with the proficiency, car, and attention their heavenly proportions deserve. Watches these days are infinitely better products than their forerunners, produced with a very different goal in mind. Those designs that have, since their first presentation, given so much joy to so many, are experiencing a greater comeback than could barely have been imagined three decades ago.

And so we now exist in an era of “mature luxury”. The industry has learned from its many mistakes and we are finally seeing the fusion of classic, timeless, functional design merged with the greatest epoch of artisanal ability, manufacturing precision, and aesthetic awareness. That’s exactly why now is the perfect time to welcome back the new and improved Praesidus A-11. It is time for that classic watch, worn by so many heroes over its illustrious past, to take its place in the minds of the modern watch lover as one of the greatest, and most enduring, ever.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.